Manufacturing in Space Aspirational Industry Frontier or Science Fiction?

David W. Myers (2023 December). BlueEcho Strategies.

Full Article

In the first two decades of the 21st century, private companies have often accelerated past government programs and nation state agencies like NASA and ESA to advance humanity’s access to and utilization of space. Whether developing low-cost small satellites, reusable launch vehicles, or privatized space stations, commercial organizations are lining up investors and making bets on a range of sectors in an expanding space-based economy. According to the Satellite Industry Association, that space economy was estimated at over $384 billion in 2022 with many predicting a $1 trillion valuation by the end of the decade (BryceTech 2022).

While Internet billionaires building their own rocket companies get much of the media attention, there are hundreds of companies staking a claim in space. One area that draws both intrigue and suspicion is space-based manufacturing. So how realistic is the notion of manufacturing products at any reasonable scale in space? Will these products be primarily for use in space itself by astronauts and spacecraft? Or is there an opportunity to manufacture something of such rarity and value that the economics to build it in orbit and return it to Earth may actually be viable? Finally, is there an aspect of the space-based manufacturing sector that has tangible near term value, as a potential stepping-stone to a sustainable in orbit economy?

The Opportunity: Benefits of Manufacturing in Micro-gravity

There are two fundamental environmental conditions that are unique to low earth orbit (LEO) and provide potential manufacturing benefits. The first is micro-gravity. The second is the ability to sustain a true vacuum with zero atmospheric pressure. Chemical compounds behave differently and manifest different physical properties in micro-gravity and vacuum environments. Experiments aboard the International Space Station (ISS) have demonstrated higher quality crystal growth in micro-gravity, which has potential for building more efficient semi-conductors. Homogenous chemical solutions that would otherwise separate in the presence of gravity may have applications in medicine or chemistry. Experiments manipulating molten metal in micro-gravity have enabled the development of perfect metallic alloy spheres (think ball bearings) which could be used in spacecraft components. We have just scratched the surface on the applications for micro-gravity and vacuum enabled manufacturing (Airbus 2022).

The Means: Additive Manufacturing Offers a Flexible Approach

One particular technological advancement in recent years has increased the viability for space-based fabrication. Additive manufacturing, more commonly referred to as 3D Printing, leverages computer aided design to render virtually any shape. This approach can be used to craft entire objects or component parts that can be assembled into larger more complex products. Unlike traditional manufacturing techniques, that require specific molds or tooling to build a limited set of end products, 3D printing is virtually limitless in the configuration of shapes and objects that it can build. 3D printing also benefits from little to no waste, compared to traditional “subtractive” manufacturing, which often starts with a block of raw material (wood, plastic, metal, etc.) that carves out the desired end shape (DOE 2014).

Starting with a digital template for the design, a 3D Printer uses spools of raw material, which can vary from plastic, metallic, ceramic, and composite substances. This material is meticulously added layer by layer to create the desired structure. This reduces the cost of “waste mass” from traditional manufacturing that would have to be launched into orbit but would not be used in the end products (DOE 2014). 3D manufacturing combined with the unique properties of a near zero-g environment opens tremendous possibilities for the development of entirely new classes of products. Companies like Redwire and Made In Space, which merged in 2020, are working to commercialize zero-g 3D printing, even conducting multiple experiments onboard the ISS as early as 2014 (Foust 2020).

Outside the confines of a laboratory or habitat, space-based manufacturing may enable the fabrication of materials and fuels at masses that would be impractical to launch into orbit by conventional means. Mining the moon or asteroids for ice or other raw materials to create fuel for rockets is one important space manufacturing concept that may in fact be a prerequisite for long range interstellar travel to Mars and beyond (ESA 2020).

The Challenges: Achieving Economic Viability in Space

Manufacturing in Space is truly an industry in the embryonic stage of development. For the most part, it has been experimental and on a very small scale. As a result, space-borne fabrication has yet to demonstrate a path to profitability. Although that is to be expected at this pioneering period in its evolution. Aside from the monumental technological complexities of conducting any operation in orbit, today there are three fundamental industry challenges that must be overcome to establish viable commercial manufacturing in space:

1. Building in orbit infrastructure

2. Establishing economies of scale in space

3. Defining the value-proposition for space products

Infrastructure on Orbit

Imagine if there was no automotive industrial base. To build a new vehicle, an aspiring auto maker would first have to build a brand-new manufacturing plant and court an entire ecosystem of suppliers. This would dramatically limit the number of players in the market and reduce the choices available. The resulting scarcity would change the supply and demand dynamics resulting in much higher per unit prices — potentially out of reach for a commercial market. Essentially that is one of the key challenges for manufacturing in space today.

There are few if any actual space manufacturing facilities available, and those that do exist are not purpose-built. The main human facility in LEO is the International Space Station (ISS), but it is near end-of-life. In fact, the 2022 NASA International Space Station Transition Report, lays out a specific plan to migrate all ISS activities to future, but undefined, “Commercial LEO Destinations.” The challenge is that there really are no commercially viable platforms available at present. Much like the end of the Space Shuttle program in 2011, there may be a significant gap in years before commercial alternatives become available to replace the ISS (NASA 2022).

China launched the first components of its latest generation Tiangong space station in 2021. While just at the beginning of its orbital life, the small facility currently holds room for only half a dozen crew members. The geopolitical complexities of commercial organizations using the Chinese space station are also fraught with challenge. So to develop a space manufacturing industry, there must first be an investment in the “real estate” to build orbital factories (Space.com 2021).

Economies of Scale in Space

While rocket launches have become relatively routine, since the inception of human spaceflight in the 1960’s only about 600 people have actually made it to orbit, out of a current population of 8 billion (Pelton 2019). Thanks to companies like SpaceX, Rocket Labs, Astra, and Blue Origin the cost per kilogram to reach Low Earth Orbit has been on a dramatic decline. This lowers at least one barrier to entry for the space manufacturing market.

During the Space Shuttle era the cost to reach orbit was over $64,000 per kilogram. Today, the SpaceX Falcon-9 can lift a kilogram of payload for about $2,600. The company’s Falcon Heavy launch vehicle, with its higher capacity reportedly reduces the cost per kilogram to just over $1,500 (Our World Data 2022). However, the cost to get people, equipment, and supplies to orbit and then “rent” the ISS to conduct experiments or manufacture anything is still considerably prohibitive.

To rent the ISS from NASA for a LEO manufacturing mission requires a strong lobbying effort, patience to wait in line for a mission window, and a cost of $10M. This does not include transit or daily food and supplies which run about $2,000 per day per person, who by the way must be qualified astronauts. To get to the ISS, you would also have to hitch a ride from one of only 2 operational launch services. SpaceX charges $55M per trip. So before you have designed or built anything in space, you are looking at an initial cost of $65M or more (Space Report 2023). At these current cost thresholds, it is tough to imagine a product that would have enough value to warrant the investment of in-space manufacturing.

Value Proposition for Space-built Products

The notion of manufacturing in space is intriguing and early experiments have demonstrated that there are materials that can only be created in the micro-gravity or vacuum environment of space. However, discrete space-built products are still very much at the conceptual stage of research & development. The value proposition for space-built products is unclear. Most experiments to date have been scientific in nature and have yet to demonstrate practical products. Without a better understanding of the addressable market for space-built products, crafting a business plan with any confidence of achieving profitability will be difficult (Factories in Space 2023).

Developments that May Enable Viable Space Manufacturing

There is light over the horizon for space manufacturing. The first opportunity comes in the form of NASA demonstrator contracts to help stimulate the space manufacturing industry. Without government funded projects to mitigate the risks of venturing into truly unchartered space, aerospace giants and start-up companies alike will be hard pressed to convince their investors to take on the challenge.

In 2019, NASA awarded the company Made in Space a $73M contract known as Archinaut One. The contract is a paid development demonstrator to prove the viability of building a deployable solar panel in space. This would be a practical application of building a product in situ to repair or replace a critical component on a spacecraft. This award was a follow-on to the original Archinaut contract from 2016 (Werner 2019).

This approach is similar to NASA’s Commercial Orbital Transport (COTS) program launched in 2006. The initiative successfully prompted industry to take the risk and develop commercial launch vehicles that would eventually replace the Space Shuttle for both space station cargo resupply and crew transportation missions. SpaceX, Boeing, Northrop Grumman, and Sierra Nevada Corp now all have new launch vehicle systems as a result. NASA will likely need to continue to incubate the development of space-based manufacturing until such time as a scalable industrial base is established (Werner 2019).

The second profitability enabler is the creation of commercial facilities on-orbit. These could become permanent habitats for space manufacturing ventures. Several commercial companies are defining plans for commercial space stations that could be utilized as manufacturing infrastructure.

Perhaps the most notable are Axiom and Bigelow Aerospace. Both are in early development stages for alternative “Commercial LEO Destinations,” to use the NASA terminology. Axiom promotes its “Hab One” as the first commercial space station, noting that it is currently under construction and aiming for launch in 2026 (Axiom 2023). Bigelow’s Expandable Activity Module (aka “BEAM”) is an inflatable habitat concept in development as a commercial alternative to the ISS. Bigelow has put two experimental systems in orbit to date (Bigelow 2023). Both Axiom and Bigelow are working to create commercial Low Earth Orbit facilities that can be used by either nations or companies without space assets of their own. For manufacturing in space to become self-sustainable, multiple commercial options to rent or even buy “space condominiums” for scientific research and manufacturing operations will be crucial.

Customers of Space Manufacturing: On Earth or in Space?

According to Factories in Space, a website that includes a database and archives of research articles on the topic, the are two potential market areas for space-built products (Factories in Space 2023). While the terminology sounds a bit like something out of a 1930’s Flash Gordon movie, it does generically define space product use cases:

Earth Customers: The idea is to build novel “micro-gravity products” that cannot be replicated on Earth. These products would be for extremely high-value applications such as medicine, semi-conductors, or scientific research. To offer customer value, the quality or rarity of the space-built products would have to substantially exceed those of substitute products already available.

Space Customers: Targeting more “local users,” the idea is to build large space structures, components, materials or fuels for consumption and utilization in space. These products would not have to be configured to fit within launch vehicles or survive launch or re-entry forces. They would also offer the ability to utilize raw or recycled materials already available, rather than being dependent on resources originating from Earth.

Of the two potential markets, Space Customers represent the more appealing opportunity for venture capital investment. The scalability limitations previously noted will severely hamper the economic returns to build products in space and then return them to Earth for utilization. At least for the foreseeable future. Only extremely high-value per kilogram end-products (think diamond-like starting prices) would be candidates for a “return from orbit” business model. This means the Earth-bound market for space-built products will likely remain restricted to highly specialized niches. By contrast Space Customers represent a more practical market that may in fact already be seeing the early benefits of commercial space-based products and services.

Commercial Robotic Spacecraft: A Near Term In-Space Industry

True space-borne manufacturing may still be years away. But today there is a real business case for commercial robotic spacecraft services. The most notable application is the repair and life extension of existing satellites already in orbit. Intelsat, the world’s largest fleet operator for Geostationary Earth Orbit (GEO) communications satellites, has already demonstrated the proof-of-concept and committed to using unmanned robotic vehicles to extend the service life of four (4) of its existing spacecraft (Intelsat 2023).

To design, build, and launch a large geostationary communications satellite has an average cost of between $300M to $500M. The typical orbital life of a GEO satellite is about 15 years, which is primarily determined by the fuel capacity of the spacecraft’s station keeping thrusters (Pelton et al 2017). As the satellite begins to run low on thruster fuel in the latter years of service, the fleet operator allows the orbit to gradually go into increasing inclination. This essentially means that the formerly “geostationary” satellite no longer occupies a fixed point in the sky when viewed from Earth. The inclined orbit satellite now appears to move in a figure eight-like pattern across the sky over the course of a 24-hour period. Once the satellite’s fuel is nearly depleted, the spacecraft will make one last engine burn to lift itself into a so-called “graveyard” orbit, where it will remain as inactive space junk (Pelton et al 2017).

Once a satellite goes into inclined orbit the addressable market for its communications bandwidth is significantly reduced. Fixed satellite antenna systems on the ground, which represent the bulk of the commercial market for enterprise communications at over 3 million terminals worldwide, can no longer access the spacecraft’s bandwidth. Only vehicles or vessels equipped with complex in-motion tracking antennas can continue to access a satellite at inclined orbit (Richharia 1999).

This limits the addressable market to primarily aircraft or commercial maritime applications, including cruise ships and ocean-going cargo vessels. This is a market of approximately 42,000 endpoints worldwide. As a result, the addressable market for an aging GEO satellite, once it goes inclined, is substantially reduced to a small percentage of its size while station-kept (Comsys 2023). In addition, inclined orbit GEO satellite capacity generally commands much lower prices per MHz than comparable station kept capacity. The average wholesale cost for GEO stationary capacity over the continental U.S. in 2022 was between $2,000 to $3,000 per MHz per month. Comparable inclined orbit capacity over the same region was less than $1,000 per MHz per month (NSR 2023).

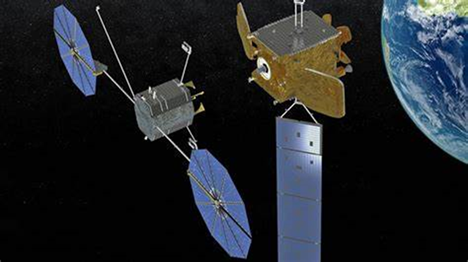

A typical large GEO communications satellite has 24 transponders at 36 MHz each for a total bandwidth capacity of approximately 864MHz. At the reduced pricing of non-station kept bandwidth, the satellite’s earning power is reduced from up to $30M per year to less than $10M per year, once the satellite goes to inclined orbit (Satellite Today 2023). For a fleet operator, the peak earning period for the large capital investment of a GEO satellite is in the first 10 years of a 15-year orbital life. To increase the return-on-investment horizon, Intelsat has turned to Mission Extension Pods (MEPs) manufactured and operated by Northrop Grumman’s Space Logistics division. As illustrated below, these MEPs are essentially mini-satellites themselves that latch-on to a larger spacecraft that is nearly at end-of-fuel capacity. The MEP takes over the spaceflight operations for the conjoined spacecraft, allowing the geostationary orbit to be maintained for a further 5 years, or potentially longer (Northrop Grumman 2023).

(image credit National Space Society 2019)

While not “per se” Manufacturing in Space, services from specialized robotic spacecraft, like Northrop Grumman’s MEPs are one of the first practical applications for commercial space operations. Whether for communications satellites, Earth observation spacecraft, or future space habitats, extending the service life of costly orbital assets improves the economics and sustainability of the industry. The Intelsat/Northrop Grumman partnership demonstrates that when there is a compelling business case for space-borne products and services, commercial companies will find a way to capitalize on the opportunity.

Conclusion: Still a Reach Yet Closer Than It May Seem

It may be difficult to imagine creating rarified materials in orbit for use back on Earth. However, Manufacturing in Space is very likely a prerequisite for true deep space human exploration. Building spacecraft components in situ or refining raw materials from an asteroid for fuel sounds like the stuff of science fiction, but it may be closer to reality than one might think.

Recent use of commercial robotic spacecraft to extend the service life of aging communications satellites demonstrates that when a compelling business case is present, industry has the technical capability and financial will to make it a reality.

Developing the industrial base necessary to make Manufacturing in Space scalable will take time, patience, and more than a few lessons from unintended outcomes. To truly enable the development of a sustainable space-based economy, the pioneering private companies who have accelerated humanity’s cosmic presence over the past two decades, will likely remain dependent on nation-state agency initiatives for a while longer. Government sponsored programs or public-private partnerships will be critical to balance the risk of launching new business ventures into the final frontier.

References

1. Airbus (2022) In space manufacturing and assembly | Airbus

2. Axiom (2023) Commercial Space Station — Axiom Space

3. Bigelow (2023) Expandable Activity Module. Bigelow Aerospace

4. BryceTech (2023) SIA State of the Industry Report. BryceTech — Reports

5. Comsys (2023) COMSYS VSAT Report, 13th Edition. www. comsys.co.uk

6. DOE (2014) How 3D Printers Work | Department of Energy

7. ESA (2023) Off-Earth manufacturing: using local resources to build a new home ESA

8. Factories in Space (2023) — Making products for Earth and space. www.factoriesinspace.com

9. Foust J. (2020) Redwire acquires Made In Space — SpaceNews

10. Intelsat (2023 June) Intelsat To Sustainably Extend Life of Four Satellites By 2027 | Intelsat

11. NASA (2018) NASA Administrator Statement on Space Policy Directive-3 — NASA

12. NASA (2022 January) International Space Station Transition Report. NASA.org

13. National Space Society (2019) Satellite Life Extension Becomes a Real Thing — NSS

14. Northrop Grumman (2023) Mission Robotic Vehicle (MRV) Satellite Technology | Northrop Grumman

15. NSR (2023) Consumer and Enterprise Broadband via Satellite, 22nd Edition — NSR

16. Our World Data (2022) Cost of space launches to Low Earth Orbit). Oxford University

17. Pelton J. (2019) Space 2.0 Revolutionary Advances in Space Industry. Springer

18. Pelton J., Madry S., Camacho-Laura S. (2017) Handbook of Satellite Applications. Springer

19. Rich D., Schertz J., Hugo A. (2020 January) The Space Resource Report — Space Resource

20. Richharia M. (1999) Satellite Communications Systems 2nd Edition. McGraw-Hill

21. Satellite Today (July 2022) — GEO 2.0: The Future of Geostationary Orbit | Via Satellite

22. Space Report (2023) Human Activities in Space Archives Space Foundation

23. Space.com (2021) China launches core module of new space station to orbit. space.com.

24. Werner D. (2019) NASA awards $73.7 million to Made In Space for orbital demonstration — SpaceNews